B O L D O B L I Q U E

| game reviews | ✭ | my games | ✭ | the stacks |

| abandoned games | ✭ | places i'm published | ✭ | about |

Inscryption

Mid-Game Review

I'm not sold on the phraseology of "Spoiler Warning" because sometimes I quite like it when someone just tells me about what happens in a game. So, I'm taking a page from the meteorologist's book and downgrading this from a Spoiler Warning to a Spoiler Watch.

To be clear I will be speaking about many things which I believe are better experienced yourself than via my narration—plan accordingly.

————

Start without me, starting without me, or started without me. I've been struggling with verb conjugation recently. The cause is unrelated to Inscryption. I struggle with card games.

Inscryption is a deck-building card game. I struggle with card games like I struggle with skateboarding games. They require a little Brain Use. Not the easy kind of Brain Use like floating through a multiple choice test, but actual effort. Effort to learn, to practice, to make mistakes and to say "Ok, how could I maybe avoid this mistake later?" These are habits not exactly encouraged in the mind of the Gifted Student Smart Boy. In fact, such habits might be so well in-grained that one burdened with them would naturally seek out the path of least resistance. In this case, the resistance of the risk of failure. The fear of it. Come to think, these same habits could possibly also form in someone who was over-punished for failing, one might learn to resent challenges which represent the risk of rejection.

For example, I just now caught myself on the edge of sneering at some footage of high level Tony Hawk play. A video my partner put on which demonstrates how to unlock the mirror deck in Roswell (if you understood that sentence please come to my house!!! My boyfriend is lonely without someone to Talk Hawk.) I decided to experiment. I thought, "Wow, this is cool gameplay. I could learn this if I applied myself. I bet with a little practice this would appear to me as Chill and Neat rather than Intimidating. It's just a game I haven't spent time with." It made a difference.

This same difference I hope to make in my tackling of what I assume is the second half of the game. I have spit every deck-builder video game I've tasted out of my mouth since forcing myself to finish Kingdom Hearts: Chain of Memories on mute during fugitive late-night play sessions on a contraband Nintendo DS at a remote children's home when I was fourteen. I'm just not that good at working out synergies!

Like pulling teeth

Inscryption begins with a bold, simple, lovely little idea. A real jawbreaker of an idea so good you want to steal it but so simple you could never get away with it. There's no new game button on a fresh profile of Inscryption, you initialize the game by pressing Continue. It's fabulous. The game declares its aspirations to mystery, to nonlinearity.

An unseen male voice accompanied by a bit of VHS video effects mutters something and we begin.

I am in the dark. Under me is a chair. Before me, a table. Across the table from me, a pair of watching eyes. I can see nothing else of the figure across the table. There is a weighing scale, there are cards, a candelabra, and a small ornate receptionist's bell.

The figure and I are playing some kind of game. It is a card game. I realize I am going to play this card game with a first-person perspective. A second realization follows the first: all card games are played in first-person. This is important to the Inscryption experience but we can talk about that later.

The figure across the table from me, the pair of eyes in the dark, teaches me the rules. His dialog appears as text but the general atmosphere and the quality of the writing lead me to imagine his voice as husky yet sonorous, slow yet pointed. He walks me through the basics by have me play cards at his instruction. I watch the cards work. A squirrel is free to play. A wolf costs sacrifices. The squirrels are discarded to make way for the predators. The animals on my row attack my opponent. Soon, I'm laying down squirrel cards, wolf cards—other animals. I draw a stoat card. The text on the state card changes. It addresses me.

I can see the dark figure over the tops of the cards in my hand. He grows impatient as I read the stoat's words. The stoat is unconvinced at my playing ability. He will remain a fixture of my deck and occasionally comment on my plays.

The game is like Magic The Gathering, I think. I lay down creature cards, woodland animals, to fight through my opponent's creatures or to deal damage to my opponent directly. The damage dealt is visualized as a massive metal scale sitting on the table. One side of the scale, or pan, is his and one is mine. When we receive damage, that many weights are added to our pan and whoever's pan hits the table surface first loses. Rather than accruing damage as separate amounts like in a conventional battler, we experience a tug-of war-like scenario. I like the drama.

I realize soon that the card game matches we play are merely episodes of a longer game. Between battles the dark figure unrolls various maps which trace a dotted line course through a dark wood. I move a wooden game piece along this map, occasionally triggering a card match but also landing on spaces which give me new cards, upgrade cards, or expand my items. Each map ends on a boss fight, victory over a boss unlocks the next map. I have a three-slot inventory of usable items. Quite devastating stuff like pliers for pulling a tooth to literally tip the scale or a pair of ornate scissors with which to fully slice an opponent's card in two and remove it from the game.

When I enter a battle, an instance of the card game, the dark figure is my opponent, playing with his own deck. However, the dark figure across the table will also provide narration for my little figure as I move it along the path. He describes my deck of cards and the journey of my token across the map as though I were literally walking this path surrounded by a group of helpful animals. Each stop arrives with colorful descriptions of the setting, creepy ritual alters, and campfires surrounded by "survivors" eager to eat my animals if I stick around too long. So, he is both CPU opponent and Dungeon Master, guiding me through an eerie scenario.

As we progress I slowly learn that I cannot leave this cabin, although, I am allowed to get up between games to fiddle with this and that around the room. A cuckoo clock, a safe, a cabinet with puzzle drawers. Not a surprising collection to belong to my puzzle-obsessed host.

On each segment of the map (the dark forest, the swamp, the icy mountain, and path to the cabin) I am allowed one failure. On the table is a candelabra with two lit candles. One loss of a battle and one candle is blown out, two and it's Over. When you enter a boss battle with two lit candles he will blow one out on principle. When you begin a new map the candle is relit.

A cutscene of your character being turned into a card (which can reappear in subsequent runs) plays when you lose your second candle flame. The dark figure asks you for your name every time and dialog around the begining of later runs indicates you are now playing as a different person. Perhaps one who has wandered into the cabin, drawn by the light.

When you finally reach the end of the maps you make your final play against the dark figure. He is revealed, or confirmed, to be some kind of woodland god obsessed with "inscrybing" creatures into cards with his magic camera.

I'm feeling good about this battle. I've failed enough, learned different cards types enough, gathered my favorites and even developed a couple little strategies. This is great. I like this card game!

After you defeat his first couple rounds against you, wherein he changes identity to become one of the previous bosses with their unique mechanics, he makes his last desperate gambit. His last move in the fight is to make the moon itself into a final card. I brace myself, read the table and find... oh shit I'm going to beat him. As I make a couple adjustments to my spread I think that if I lose this attempt I might feel discouraged enough not to try again. I watch the numbers change, my last couple turns are just skips, victory is inevitable. That same unseen male voice remarks that he finally beat him.

It's this defeat where the game turns, suddening, shockingly, into something else.

We see a grouping of video clips. A try-hard collectable card gaming youtuber sits before a green screen making pack opening videos. Here's the voice we've heard twice. He shows us packs from a discontinued game called "Inscryption." We raise an eyebrow when he off-handedly mentioned a "blue mage" card in the pack; that's not any card we've seen in this game within a game. One of his packs has been opened and intriguingly resealed. It contains a card with coordinates on it (somewhere outside Vancouver, Canada.) In further clips, we see him traipsing through a thick forest, digging up a box with a floppy disc in it, and then running the software at home.

Not to be Old or whatever, but the metal flash shield on that floppy was pulled up and the magnetic disc probably ruined. Also there's no way this imaginary game could fit on a single floppy. It has sound! Why not just put it on a spooky CD-R? I suppose floppies do have slightly more akin to a mysterious grimoire than a burned CD. I remember thinking they were cool and mysterious myself even while they were in actual use. So, fair enough.

The game boots.

It's the Inscryption start screen, now with a usable New Game button. We enter the New Game and oh God. Oh no. I mean, with the live-action clips and various other gestures towards the meta I expected something new, but this...

There's some narration indicating the dark figure, the woodland god, is one of four powerful entities that each have a different method for making things into cards. There's a robot guy, a wizard and one other. Alas, this means there are like four completely different ways to play the card game. I'm downcast. I feel myself pushing hard against learning yet three more ways to lose at a goddamn deck builder.

The next leg of the game begins. I'm a little character in a 2D, pixel art world moving a around a map. It quickly clicks, we are doing a pastiche of the Game Boy Color title, Pokémon Trading Card Game. Ok, that's interesting at least. The play field of the card battle segments is a flat, pixely mess with more information crammed into a smaller space. Not to point out the obvious, but adding a third entire dimension really lends a feeling of spaciousness you just can't get anywhere else. Now, I feel reduced as I try to follow the action.

Furthermore, because three new types of play, with new card types and dozens of new cards. The new cards all possess their own mechanics and strategies. It appears they are just a part of the deck ecosystem and I have to work out how they function on the fly. God, I know how frustrating I am. It's not really a stretch to imagine the reader who encounters my histrionics and thinks "New cards? New deck types? Game Boy style? Learning on fly!? SIGN ME UP!!"

I will make an admission: the strawman I've stuffed here is probably going to have a better time and better understand this game that I have any hope to with my current mindset.

It's these feelings of frustration, and the impulse to yield to them, is the real struggle here. I have, victoriously, finally recognized this impulse as a particular position to take rather than the unspoken default mindset. I am smart, I am a hardworker; those things more or less come to me easily and frankly I rarely stretch myself to accomplish anything so long as Good Enough is acceptable. Maybe I learn new methods and work myself to death but rarely, rarely, rarely do I honestly challenge my self-conception. Even in the smallest way: by saying I might need to practice something before I can get it. I, like plenty of people, am averse to the risk. I just don't want to try if it's something I've already reckoned was not For Me.

Why do you suppose I started the review before finishing the game?

Playing at the Playing

There are fewer in-depth plot spoilers in this review than I anticipated. Inscryption left me thinking less about its mysterious, A.R.G.-esque story and more in the mind to ruminate on my time with the cards themselves. On every level, the cards' importance to the play experience is mechanical and aesthetic in equal measure.

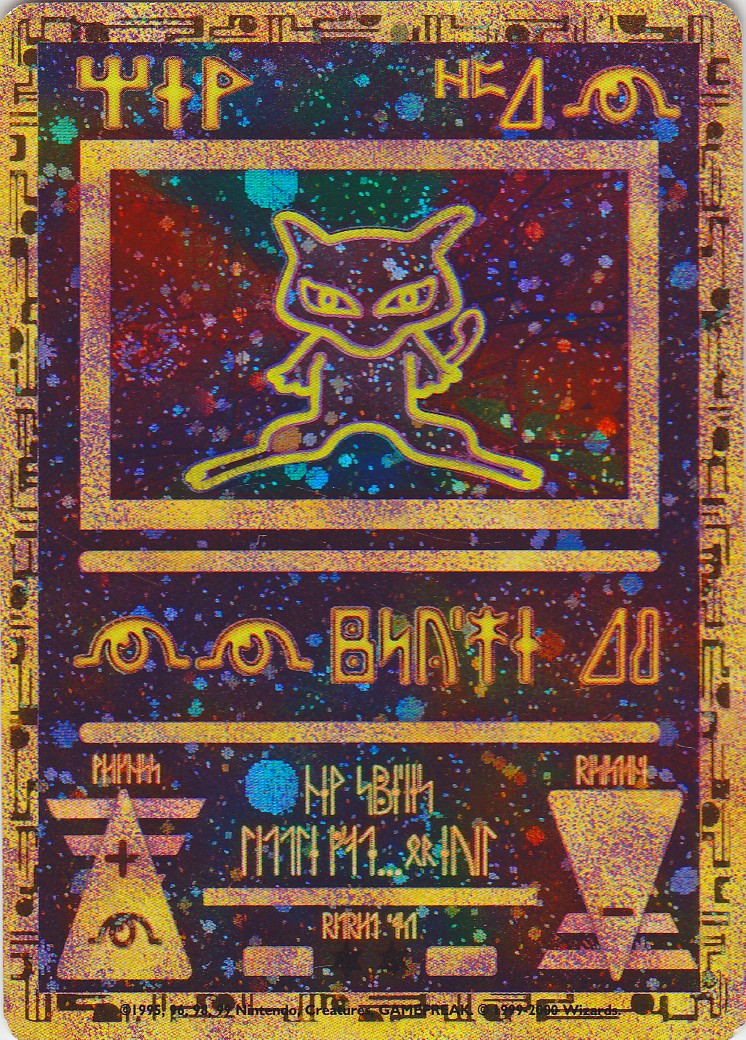

The first thing we see when we look is a collectable card game. As a kid I collected Pokémon cards in a three-ring-binder. I remember a friend on the bus who would share his collection with me. We would open our binders and gawk at each other's holographics, complete evolutionary lines, bizarre item cards, and the mysterious Japanese cards.

My favorite card was my holographic Ancient Mew, this was given out to attendees of the opening of Pokémon the Movie 2000: The Power of One. I attended a viewing of this film on my tenth birthday, the film's North American opening day, July 21, 2000 at my local theater, the AMC Colonial 18 in Lawrenceville, Georgia. The Ancient Mew card was fully holographic, rather than just the key art, and had a sparkly purple texture. It featured unreadable hieroglyphic text making it totally unusable in play, but it was my treasure.

But that's the thing, I never played the game. The first and last time I played Pokémon TCG was last year. Due to unique reasons, my friend Christian and I experienced simultaneous last days at our jobs and decided to get brunch the first Monday after. He bought me a breakfast burrito at one of Atlanta's many highfalutin-but-pretending-to-be-working-class taquerias. Afterwards, we went to his house and through a long, hazy, Autumn afternoon played several games. He explained the rules patiently and at the beginning of the second game it finally clicked with me: this is a JRPG battle.

But that's the thing, I never played the game. The first and last time I played Pokémon TCG was last year. Due to unique reasons, my friend Christian and I experienced simultaneous last days at our jobs and decided to get brunch the first Monday after. He bought me a breakfast burrito at one of Atlanta's many highfalutin-but-pretending-to-be-working-class taquerias. Afterwards, we went to his house and through a long, hazy, Autumn afternoon played several games. He explained the rules patiently and at the beginning of the second game it finally clicked with me: this is a JRPG battle.

The cards themselves are like an aesthetic over-layed on a turn based style battle system. Wherein the two combatants or teams pick their moves and execute them by taking turns. Move here can mean a basic attack, using an ability or item, managing values like health or mana, or some other maneuver allowed by the rules as part of the contest. Sometimes, these contests can grow dense and complex. In a card game, players take turns drawing cards, laying them down, using their unique abilities, and discarding them. The flow and rhythm were not just familiar to me but beloved. This observation was my In. Or it would be a year later when I decided to play the second half of Inscryption after all.

Maybe the Pokémon theme of the card game is what made it really sink it but what we're doing here is just turn-based combat. Competitive JRPG battles without a digital device. I saw my personal HP, the various monsters' moves, their individual HP, and the 'evolution' of the spread as my Pokémon grew stronger. I considered tactics. I rearranged my hand. I mulled over possible moves my opponent could make. I forced myself to use my items and not to hoard them. It was all there. "Wow," I thought, "I could have been having a pretty good time with this if I had bothered to learn to play."

It never occurred to me that my desire for a complex, involved JRPG-battle system like a good SMT (I mean good SMT, think Nocturne) could be sated by a card battler. Seems obvious now. But it was the deck-building aspect that forever stopped me. My criticism at the age of ten is basically my issue now: I'm not interested in a game which requires me to keep buying things in order to meaningfully participate.

I know they sell the pre-made decks but with any of the big card games the starter decks are not where the true game resides. Introductory products meant to help the new player learn the ropes. But even as a kid I knew the Magic The Gathering players playing at the back of the hobby shop weren't baking with a box mix. They were in the test kitchen fine-tuning their recipes by running them over and over against one another, reading lists of releases and rules, (today) purchasing single cards online, and keeping up a healthy flow of booster packs. Who has the time? And who, because I don't, can imagine how to bridge the gap between the newbie breaking into their first starter deck and the Bigger Kids and Adults who live part-time in the card shop?

The decks kept me away, and frankly the success Inscryption has had with me has been in keeping the deck-building to a minimum.

Regarding deck building, it's not just the money and the time. It's the obvious possibility of looking stupid, and the necessity of expertise. I am seriously motivated by the desire to avoid social embarrassment. On the occasions I've encountered a famous person I turned around and ran. Not happening. And if I need to familiarize myself with unknown concepts, stuff I could possibly be seen getting wrong at first, well, forget it.

This is cyclical. I've been investigating why I don't devote more time, more heart, and more criticality to the things I really care about. All the art and all the writing I've ever made, more or less, needed more time—more care and clearer eyes. But that worry about taking the time, becoming an expert, trying many times over, plus the FOMO for anything else I could be doing otherwise—I think I may have occasionally held myself back in life.

To borrow a tired Tweet format, I don't know who needs to hear this but you can be good at something even if you are not initially good at it. What do you think this essay is about?

Learning to earnestly and humbly try new things can be like pulling teeth. Incidentally, pulling teeth is very useful in Inscryption. I said the mechanical and aesthetic nature of the cards is important on every level. Beyond just overlaying the kind of contest you'd find in a good roleplaying game, the physicality of the cards and the player's position as a table-seated participant shape the experience as much or more than the universal battle mechanics like HP.

The nature of a stack of cards is that cards are evenly cut and printed pieces of cardboard which exist in a physical universe. The backs of the cards are the same, this anonymizes them. The deck can be shuffled. In most games it must be shuffled. When a card is no longer in play it is placed in a discard, this in many games becomes another resource you may use. Tokens and small markers are often used to keep track of this and that. Inscryption is such a good game because it doesn't forget those aspects. At least, in the 3D, table sitting portions.

We toss teeth on the scale to track who's winning. We get up from the table to fidget with the curios of the forest god's cabin. We free resource cards from old glass flasks when we need them in a pinch. We blow out candles. We solve sliding puzzles (like Chess puzzles, the sliding plates suppose an Inscryption game in progress) to receive new cards or mysterious items. We mix and match pieces of various little wooden totems which stand proudly on the table and mix up the game's rules. We use old pliers to extract a tooth from our mouths now and then. You see, a single tooth weighs about as much as one point on the scale and it can help move things in our favor. Eventually, we unlock a knife to remove an eye which gets plopped on the scale. Heavier. More points. How Egyptian.

It all lives on the table. In first person view. The camera work with the arrangement of the elements of the table creates a perfect tableau. It is both artistically pleasing and immediately informative as to the state of the game. It is as well arranged as the elements of the battle screen of Dragon Quest I and I do not say this lightly.

Daniel Mullins crafted a masterful introduction to the game and the story. It is a tutorial as much about familiarizing the player through doing rather than telling as it is a tight prologue to the greater world of the game. The developers very smartly allowed the nature of the cards as objects and the material nature of the world to draw us in. The subversive feeling of using non-card items like scissors to cut my opponents cards to pieces or the afore-mentioned pliers, led to an excitement which made the rest feel more accessible. This is not a discussion of accessibility in games, just my own biases.

Well

It's over. Many new cards and styles of play have been introduced. Characters have appeared, made themselves understood, and exited. The poor YouTuber is laying in a puddle of his own blood and I am watching the credits roll by.

I love the ending, and it was obviously the ending. A conclusive ending to our protagonist's journey and a suggested end of the characters of Inscryption itself. All of whom I came to like and sympathize with, even if that characterization may have been slightly less delicately woven into the ending as it had been in the middle. There's a lot of quick pathos at the end. Playing against the goddess of death with her unique chess board layout and gorgeous headstone-inspired card designs was fun. But one last game with the woodland god, the dark figure from the beginning, was immaculate. My old friend who seemed spooky but was just in it for the play. He seems to accept his fate less well than the goddess of death but far more gracefully than the wizard.

I know there's more to dig into, a new option on the start screen invited me to check out a "mod" for the game created by the in-fictional designer of the Inscryption video game (separate from the in-fictional Inscryption collectable card game.) I have messed with it and it plays like a stripped down version of the main campaign with challenge options. Which is perfect. It's an excellent way to get a shot of the aesthetic and battles with some extra challenge and no fluff. I also started the, I suppose it's a kind of New Game +? There's obviously some stuff going on there but I didn't go too deep.

I want to, I mean, I want to go deeper. But also I think I got all I needed. There's a suggestion late in the game that the secret hiding in the disc had something to do with nuclear weapons and at the end we see a snippet of the data and there's some kind of government ID with a Department of Defense heading. I figure that's enough for me to put it together myself. Although, I do wish I had played on PC. The Xbox experience only delivers the gist of the data-related story stuff, or so I've been told.

I read and contemplated the description of everything I picked up in Elden Ring Shadows of the Erdtree and I was satisfied. But typically, I don't like picking apart the minutiae of something I love. Lore is not a story.

It's in the struggle; when you practice acceptance of a little struggle. Only in the teeth-pulling does the joy bubble up.

JRW 2024